- Home

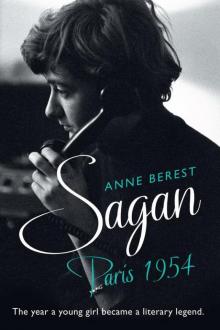

- Anne Berest

Sagan, Paris 1954 Page 2

Sagan, Paris 1954 Read online

Page 2

‘That’s just as well.’7

Smiling, and as a parting shot before closing the door behind her, Françoise calls out to her brother, ‘But I shall get published!’

At that very moment, on that fourth of January 1954, a boy of the same age – eighteen, to be precise – is recording two songs. It costs him four dollars, which he pays for out of his own pocket, and he records them in a small studio specialising in the black soul music of Memphis.

The songs are ‘My Happiness’ and ‘That’s When Your Heartaches Begin’.

Both those kids, Françoise Sagan and Elvis Presley, are going to need shoulders broad enough to bear the weight of what they are going to become in a few months’ time: two idols pursued by frenzied crowds. But today they have quite simply done something, and it all stems from there. You never lose out by just doing something; there is a chance you might even win. You have to take on board the risk of winning, and the young do not realise just what the consequences of winning can be.

6 January

This is a book I have to write quickly, and it is taking shape and gradually coming into focus.

It is to be neither a biography, nor a journal, nor a novel. Let’s just call it a story.

The idea is that it’s the story of a girl, a very young girl, writing her first novel.

I will be cataloguing the various stages in the life of a budding author: her excitement, her fearfulness, her sense of anticipation.

My book will be about the progress of another book, from the moment the manuscript is sent off to the point at which it receives a literary prize. My plan is to focus on a few days in one year, the year in which the heroine’s life will be turned upside down. With every passing day and week, the anonymous teenager will be on her way to becoming a recognised writer.

If this were a made-up story, I would have to work on the issue of plausibility in order to get the reader to accept that certain incredible things can actually happen. I mean things like a book becoming a huge success while simultaneously causing a monumental scandal; I mean things like a girl who had not yet come of age becoming a social phenomenon and the most famous Frenchwoman of her era.

But that story is true. So my task is to understand and then explain to others how implausible things can suddenly happen in life. I have to be able to show how a book can explode on the scene like a bomb, how it can burst forth like springtime, how it can have an impact like the catastrophe in a Greek tragedy.

‘Françoise,’ says Jacques, ‘are you sure you won’t be sad if your novel isn’t published?’

‘I don’t know. We’ll see. I like writing.’

‘Why do you like writing?’ asks Jacques. He can see that his sister does not envisage being met with rejection, still less with indifference.

‘To write a novel is to construct a lie. I like telling lies. I have always lied,’ she answers laughingly. ‘Come on, wish me luck.’8

I visualise this girl in the Métro, sitting among other girls. They are all dressed just like their mothers, in long coats down to their ankles, Jacques Fath-style coats in dyed wool, or tweed coats. They wear little silk scarves and have their hair tied back, revealing the few pearls round their necks – there are no pierced ears. They are all dressed severely. It is an era when the transition from childhood to adulthood is a brutal one and there is nothing in between.

Like the others, Françoise is wearing a heavy coat and a red-and-white striped blouse buttoned all the way up. She could be anything from fifteen to thirty.

This is the last stage in her life when Françoise’s face is not the face of celebrity. These are the last weeks in the whole of her existence when she is still a girl like other girls, a girl of eighteen. She doesn’t know that there’s not much of the old life left for her, nor that everything is about to be turned upside down because of what she is carrying, like a cancer, under her arm. Those sheets of paper covered in words, typed up by a friend ‘because it’s neater like that’,9 are going to change her life for good. But we’re not there yet. For the moment, I see her observing people in the reflection of the carriage windows. She feels sorry for a girl who has no ankles and whose calves go straight up and down like broomsticks. It’s unfair that some people are not beautiful, she thinks, as she is lulled by the sound of the train.

Whenever I came across people who weren’t physically attractive, I experienced a sort of uneasiness, a sense of lack; the fact that they were resigned to being unattractive struck me as being an unseemly failing on their part. For, after all, what was our aim in life, if not to be pleasing to others?10

Françoise had got on at Wagram and had changed at Saint-Lazare, finally to emerge at the exit in Rue du Bac, where the wind blew up under her coat. Turning right into Rue de l’Université, she walks along to number 30, the premises of the publisher Julliard. Her hand is frozen when she pushes open the massive green door, tottering as she does so. She turns round. There is a young man behind her. They barely exchange glances but both guess that they are there for the same reason.

So they approach the desk together and naturally the receptionist addresses the young man.

‘Are you here to submit a manuscript?’

‘Yes,’ he replies timidly.

‘Don’t bother phoning for a reply. You’ll get a letter in a few weeks. If your manuscript is rejected, you can come back here and pick it up.’

‘But I don’t live near Paris,’ he replies.

‘In that case, come back with some stamped addressed envelopes. Thank you, and good day to you, Monsieur. Good day, Mademoiselle.’

The young man hurries out in search of a post office and some stamps. Françoise waits politely; she waits patiently and graciously, still facing the woman, who has buried her nose in her work again. ‘So sorry, I thought you were with the boy!’ exclaims the receptionist when at length she realises her mistake.

‘It really doesn’t matter,’ replies Françoise. ‘It really doesn’t matter at all. Please don’t apologise.’

Now we see Françoise (somewhat lighter, having been relieved of one manuscript) trotting off in the direction of the Librairie Gallimard, the high temple of publishing. This august establishment is only a short walk from Julliard, at number 5 Rue Sébastien-Bottin – the street is called after the man who gave his name to a directory of commerce and industry.

There is no one at reception. She hesitates. Her friend Florence works there but only started a few days ago. It would seem too casual just to wander off down the corridors looking for her.

So Françoise waits, politely, patiently and graciously. A young woman, hurrying past, asks her if she is there to drop off a manuscript. Françoise nods. The young woman reaches forward automatically to take the yellow folder and then declares in a single breath, ‘Don’t bother phoning for a reply you’ll get a letter in a few weeks and if your manuscript is rejected you can come back here and pick it up.’

Françoise’s next port of call is Éditions Plon, based in Rue Garancière, a quiet little street that doesn’t get too much sun, a pleasant street, its name evoking that of a flower.

I can hear Françoise’s footsteps. She is slightly out of breath, wondering, like someone wagering on several numbers in roulette, which number will come up. Which publishing firm will turn her destiny upside down? I see her frail little form, head down, lost in thought when her path crosses that of two men preoccupied by weighty matters.

The two men are of equal height.

The first man is all forehead: it is wide and pale and underneath it is a birdlike face. His beard and large spectacles seem almost to have been stuck on, the features beneath them being so chiselled. He is assistant director at the Musée de l’Homme and, apart from his thesis, he has still only published a single work, with Presses Universitaires de France. Yet, at forty-six, he is no youngster. The second man, the one whose hands dart hither and thither in the air like insects, has his heart set on bringing out Tristes Tropiques. This fledgling publisher, much y

ounger than Claude Lévi-Strauss, has black, unruly locks and a generous mouth. Strikingly handsome, he is the first man to have reached the geomagnetic North Pole. Jean Malaurie is launching a new series for Plon, entitled Terre Humaine. He wants it to be the home for a new type of intellectual: author-explorers, men defined solely by the terrain they have covered. It is this editorial dream that the explorer of Greenland is explaining as he walks along Rue Garancière, with the Senate behind him, while young Françoise passes them coming from the opposite direction, her ankle boots click-clacking on the cobbles.

Françoise goes into an imposing mansion, the Hôtel de Sourdéac, which houses a printing works whose presses are always running at full tilt. But there is also on the premises a publishing firm, one that has made itself particularly receptive to literature and essays, called La Librairie Plon, les petits-fils de Plon & Nourrit.

On entering the courtyard, Françoise is overpowered by the smell of fresh ink, which then catches her by the throat as it mingles with the scent worn by the young woman at reception. Jolie Madame, the latest perfume from Pierre Balmain, is a mixture of violets and leather and has been popular as a gift this last Christmas. Jolie Madame goes through the same rigmarole as her predecessors: Are you submitting a manuscript? You can expect a letter. You’ll hear nothing for several weeks, etc.

The die is cast. With her arms now free and swinging by her side, Françoise crosses Place Saint-Sulpice in the cold of that sixth of January. All she is thinking of is dinner that evening, when her big sister Suzanne will be celebrating her thirtieth birthday.

As happens every year, her mother will have bought a huge galette des rois, still warm. And as happens every year, everyone will make sure that Kiki finds the charm hidden in it and gets to wear the crown.

To Françoise, thirty seems a lifetime, too far off to contemplate. She doesn’t know that, by the age of thirty, she will have been married and divorced twice, will be a mother, and a writer acclaimed throughout the world, her work adapted for the cinema by Otto Preminger, acted by Jean Seberg and sung by Juliette Gréco; she will be both loved and loathed and, in a terrible accident, she will have come close to death, a place beyond the reach of memory.

Between now and the age of thirty she has so much to experience.

Suddenly I visualise Françoise in the radiance of youth. I am more than thirty now and I feel out of place as – on the run from my own life – I immerse myself in the life of another. I am following in the tracks of a child; I see her cross the square by the side of the church of Saint-Sulpice. She crosses it diagonally, passing close to the fountain and its lions.

Fully preoccupied as she is by the thought of the birthday present she is planning to give her sister, Françoise does not know that she is being watched from behind the façade of the church by the painting by Delacroix.

It is of Jacob wrestling with the Angel.

His raised knee is a sign of his will. His muscular back tells of his resoluteness. And his arm and shoulder bespeak his determination to fight. Every sinew in the magnificent body of the man called Jacob is straining towards victory and, at daybreak, he will gain God’s favour because he, a natural man, has wrestled with the supernatural. But his thigh will be for ever marked by the injury he has sustained.

In every combat undertaken, in every task completed, in every victory gained, one must accept that something will be lost.

In every task completed.

In every combat undertaken.

One must accept that something will be lost.

What shall I lose through this book?

11 January

I was immersed in the writing of my third novel when, more than ten days ago now, Françoise Sagan’s son suggested that I should write a book about his mother. Denis Westhoff is a man of around fifty. Listening to him talk is very pleasant: he speaks rapidly, in a soft, staccato tone, without any hesitation, like the needle of a sewing machine regularly piercing felt.

‘We will soon be marking the tenth anniversary of her death, ten years already, and I would like people to remember just what the publication of Bonjour Tristesse represented for society back in 1954. That was sixty years ago!’

This proposition is like a sign; it is obvious to me that this is something I must do. I drop the book I’m working on for her, for Françoise.

I phone Édouard because I am delighted to tell him the news. But we argue: he says that I feel flattered to set my name alongside Françoise Sagan’s and that I should guard against vanity, etc.

I send him an email telling him how hurt I am:

Sometimes your friends attack you with cruel words that hurt. But because they aim true and see in you the things you keep most hidden, they say, ‘It’s because I care about you that I can see the part of you that you would like to hide. And, seeing that side of you, I still go on caring about you. Perhaps I care about you even more, knowing what I do. Because you and I are alike, united in guilt.’

When your friends act like this, they bind you to them more strongly than by any declaration of love.

But when your friends attack you and their aim isn’t true, when they are aiming at other people (usually themselves) through you - that’s to say, instead of looking at you, they are looking in the mirror - that’s when your friends become terribly remote from you.

Édouard phones me back to say that there has been a misunderstanding and that I have misrepresented what he has said. He gently mocks the emphasis I put on our being friends, something I have done regularly over the nigh on fifteen years that we have known each other. We make up by having lunch in the little Italian restaurant at the entrance to the library where I work.

Édouard knew Françoise Sagan. He tells me the things he remembers about her – he does an imitation of how she used to answer the phone in a Spanish accent in order to weed out unwanted callers informing them that ‘Madame Sagan is not in.’ I say to him, ‘You loved her so much, so I don’t understand why you shouldn’t be pleased that I – your friend – am writing a book about her.’

‘Of course I’m pleased,’ he replies, ‘but that’s not the problem. What annoys me is that you’re abandoning your novel.’

Édouard is a generous soul, just as Françoise was.

So, for the last ten days roughly, whenever someone asks me, ‘What are you up to at the moment? Are you writing anything?’ I answer, ‘Yes, I’m writing a book about Françoise Sagan.’

Like a chemical reaction, people’s initial response is always the same: it’s as if a combination of certain words automatically produces a smile.

Utter the name ‘Françoise Sagan’ and you will see a smile come over people’s faces, the same smile you would see if you were to say, ‘Will you have some champagne?’

I am wondering whether, in agreeing to write about her, I am not going to put myself in an impossible position by touching on what belongs to everyone. All of a sudden I am afraid of this book.

Yesterday when I put a whole series of questions to Denis Westhoff (What perfume did she wear? What year was it that she met Pasolini? Where was her brother Jacques living in January 1954? etc.) he said something very important.

‘My mother was never afraid.’

‘Even in 1954, when she was just a young girl, before her first book came out, do you not think she was afraid?’

‘No, she wasn’t afraid of anything or anyone.’

‘But she must have wondered whether she would get good reviews.’

‘It was one of the things she taught me. Not to be afraid.’

I make a note in my work-book: ‘A scene to show that Françoise Sagan was never afraid of anything.’

I make a note in my head: Must teach my daughter that the only thing to be afraid of is fear itself.

Clearly, in my hands, there is a danger that Françoise Sagan might be lost to view. I am appropriating her for myself, just as a portrait painter imposes his own profile on the portrait of the sitter.

I am going to slid

e her into my bed with its rumpled sheets, there to wipe away the anguished sweat that, though I attribute it to her, is so like mine. She may not be afraid, but I am. So I let my black hair intertwine with her fairness and, like a photographer using light-sensitive paper, I develop the outlines of a silhouette that, while grave, is full of joy. I can’t help myself. If it’s a problem, all anyone had to do was not to ask me in the first place.

It is 11 January 1954.

It is so cold outside that Marie Quoirez, Françoise’s mother, has agreed to lend her daughter her fur coat, made from the silvery pelts of squirrels which, even after death, do not lose their ash-grey colour, while the belly remains as pale as Snow White’s thigh. The fur coat is so big on Françoise that Marie pictures her daughter as she was eighteen years previously, a gift from heaven, a newborn baby wrapped in a blanket.

Jacques is expecting her to join him for dry martinis at the Hôtel Lutetia. In the taxi taking her across town, Françoise is deep in thought as she looks out of the window at the succession of illuminated signs adorning Haussmann’s buildings: ‘Frigeco’, ‘Paris-Pêcheur’, ‘Chocolat Suchard’, ‘Janique’, ‘Gevapan’ and, especially, ‘Grand Marnier’, advertised in that Gothic script that makes you want to be sipping a liqueur in front of a log fire.

The taxi carrying Françoise drives alongside the courtyard of the Palais-Royal, as yet devoid of Buren’s columns, then past the Louvre without the addition of the Pyramid and the Jardins du Carrousel without Maillol’s bronze statues. By day Paris is sooty black. At night she is navy blue.

Françoise enters the Lutetia through the revolving doors, which muffle the noise from outside and give you the feeling of moving into a world wrapped in cotton wool. Her feet go trotting over the chequered marble floor of the luxury hotel. She recalls that, at the Liberation, a girl Jacques was engaged to at the time, Denise Franier, whose surname before the war had been Frankenstein, had been driving them through Paris in a mustard-coloured Rovin D4. As they passed the hotel she had told them it was there that whole families were awaiting the return of their fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters and children, and news from Poland and Germany.

Sagan, Paris 1954

Sagan, Paris 1954